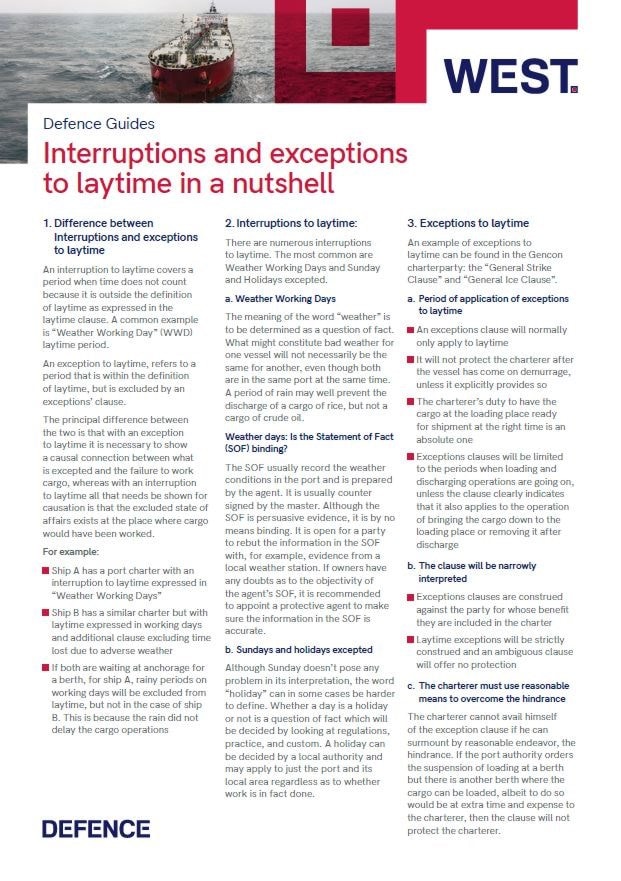

Defence Guide - Interruptions and exceptions to laytime in a nutshell

1. Difference between Interruptions and exceptions to laytime

An interruption to laytime covers a

period when time does not count

because it is outside the definition

of laytime as expressed in the

laytime clause. A common example

is “Weather Working Day” (WWD)

laytime period.

An exception to laytime, refers to a period that is within the definition of laytime, but is excluded by an exceptions’ clause.

The principal difference between the two is that with an exception to laytime it is necessary to show a causal connection between what is excepted and the failure to work cargo, whereas with an interruption to laytime all that needs be shown for causation is that the excluded state of affairs exists at the place where cargo would have been worked.

- Ship A has a port charter with an interruption to laytime expressed in “Weather Working Days”

- Ship B has a similar charter but with laytime expressed in working days and additional clause excluding time lost due to adverse weather

- If both are waiting at anchorage for a berth, for ship A, rainy periods on working days will be excluded from laytime, but not in the case of ship B. This is because the rain did not delay the cargo operations

2. Interruptions to laytime:

There are numerous interruptions to laytime. The most common are Weather Working Days and Sunday and Holidays excepted.

a. Weather Working Days

The meaning of the word “weather” is to be determined as a question of fact. What might constitute bad weather for one vessel will not necessarily be the same for another, even though both are in the same port at the same time. A period of rain may well prevent the discharge of a cargo of rice, but not a cargo of crude oil.Weather days: Is the Statement of Fact (SOF) binding?

The SOF usually record the weather conditions in the port and is prepared by the agent. It is usually counter signed by the master. Although the SOF is persuasive evidence, it is by no means binding. It is open for a party to rebut the information in the SOF with, for example, evidence from a local weather station. If owners have any doubts as to the objectivity of the agent’s SOF, it is recommended to appoint a protective agent to make sure the information in the SOF is accurate.Although Sunday doesn’t pose any problem in its interpretation, the word “holiday” can in some cases be harder to define. Whether a day is a holiday or not is a question of fact which will be decided by looking at regulations, practice, and custom. A holiday can be decided by a local authority and may apply to just the port and its local area regardless as to whether work is in fact done.

3. Exceptions to laytime

An example of exceptions to laytime can be found in the Gencon charterparty: the “General Strike Clause” and “General Ice Clause”.

a. Period of application of exceptions to laytime

- An exceptions clause will normally

only apply to laytime

- It will not protect the charterer after

the vessel has come on demurrage,

unless it explicitly provides so

- The charterer’s duty to have the

cargo at the loading place ready

for shipment at the right time is an

absolute one

- Exceptions clauses will be limited to the periods when loading and discharging operations are going on, unless the clause clearly indicates that it also applies to the operation of bringing the cargo down to the loading place or removing it after discharge

b. The clause will be narrowly interpreted

- Exceptions clauses are construed

against the party for whose benefit

they are included in the charter

- Laytime exceptions will be strictly construed and an ambiguous clause will offer no protection

The charterer cannot avail himself of the exception clause if he can surmount by reasonable endeavor, the hindrance. If the port authority orders the suspension of loading at a berth but there is another berth where the cargo can be loaded, albeit to do so would be at extra time and expense to the charterer, then the clause will not protect the charterer.

d. Do General exception clauses apply to laytime and demurrage?

It is doubtful that a general exception clause would apply to laytime and demurrage unless specifically stated. A typical example is that contained at clause 19 of Part II of the Asbatankvoy where the wording is too general and the laytime and demurrage provisions have their own code of more limited exceptions.

There is however an argument that such clause could constitute an exception to laytime and demurrage, if a general exception clause refers to delay in loading or discharging and there is no other separate code of laytime and demurrage exception.

4. Fault of the shipowner

a. What period of time can charterer

claim for?

Laytime and demurrage will not run when the delay is caused by the fault of the shipowner. The delay and the cause of the delay must however be contemporaneous and will not include consequential delay. Only where the charterers have been deprived of the use of the vessel at a time when they wanted the use of her, will time be suspended. For example, where time is lost because a berth is no longer available because of an earlier fault of the owner, charterers will not be able to suspend laytime or demurrage for the time waiting for the berth. Charterers may however have a claim in damages for breach of a separate obligation under the charter.

b. What does “fault” mean?

The mere fact that the shipowner by some act of his prevents the continuous loading or discharging of the vessel is not enough to interrupt the running of the laydays; it is necessary to show also that:

There a breach of obligation on the part of the shipowner

The delay must be for a duty for which he is directly responsible under the charter or for which he has delegated his responsibilities

The fault must be the only or the only effective cause of the delay

The delay must not be beyond the control of the owner and the owner must do nothing voluntarily to prevent the ship from being continuously available for cargo operations

In addition laytime or time on demurrage will not run if owners voluntarily prevent their ship being continuously available for cargo operations, whether or not such operations are planned by the charterers

If under a charter, owners are responsible for the stevedores, any time lost as a result of stevedore’s negligence will be for owners’ account. However if the cause of the delay is beyond the control of the owner, such as a stevedore’s strike, the owner will not be responsible for the delay.

If de-ballasting or ballasting delay cargo operations and it is not necessary for these operations to be carried out but are done for the convenience of the shipowner then the time lost will be due to his fault and will not count.

If a ship grounds due to the negligence of the crew then time will be suspended. Conversely time will count if the grounding was not due to the negligence of the crew.

Time lost for non-production of a bill of lading at discharge port will not count unless the charter obliges the owners to accept an LOI.

c. Can the fault of the owner be excluded?

Fault of the owner can be excluded however the clause would have to be very clearly worded. Clauses incorporating the USCOGSA or general exception clauses which make the owner not liable for delay arising from acts, neglects of the master and other servants of his in the navigation or management of the vessel, will not be sufficient to exclude the fault of the owner.

-

Interruptions and exceptions to laytime in a nutshell PDF (114.5 KB)